Michel Boudart

Michel Boudart, who passed in 2012, was a chemist of extraordinary character. (Boudart obit) His special area of interest was in catalysis and behaviours of hydrogen. I was privileged to become a friend late in his life and was given more than a few private tutorials on ‘spillover hydrogen’ ideas in long lunches with Michel at the Stanford faculty club. I had sought him out when I first learned of ‘spillover hydrogen’ strange chemical effects. This interest came of course from my work on cold fusion where the strangest of all hydrogen effects are prevalent.

When I first e-mailed Prof. Boudart I was of course uncertain as to whether he would be willing to chat with a cold fusion experimentalist. To my surprise he was and in our first of many lunch meetings I discovered that he’d in fact been a member of the DOE panel on cold fusion in the earliest of its days. He revealed that he was convinced there was a true trail to follow in cold fusion and so our friendship began.

There is nothing better in the life of an experimentalist/explorer than being given private tutorials by the grand masters in fields of science. Such access is never given lightly by those masters but if you are truly working in a field they know and have results and ideas to share then there is a natural bond made possible with the right catalyst, the common passion for discovery. I was working with cold fusion catalysis so that was my side of the magic required. Michel liked one particular table at the Stanford faculty club and great ideas along with a glass of Stoli which was his favourite catalysts.

As he explained to me the science of catalysts is as much black magic as it is science. He explained, “there are far too many mysteries in catalysts that have no answers to think it can be reduced to simple science. It’s far more like fine cooking. The same recipe can be prepared by many chefs but some rare few of those chefs provide a far more delicious result than most.”

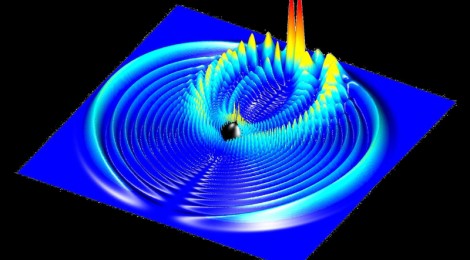

Spillover hydrogen is, as Michel explained to me, a form of singlet hydrogen that is created by catalytic particles and ‘spills’ off the metal particle onto the surrounding surface/support on which the particle is perched. The magic of a great catalyst is to make it remain monatomic and therefore highly active. The mystery is how readily spillover catalysts share electrons with passing chemistry, frequently an order of magnitude more readily than expected.

Hydrogen as we know is a single lonely proton with a very promiscuous single electron partner. Two hydrogens, its native form, provides a friend under the same roof as it were resulting in the electron staying home. The issue with wandering electrons from a protons point of view is just what are you if you are a proton without an electron, surely you are no longer a member of the atomic family. For more on the proton.

Once hydrogen is in its singlet state it really doesn’t want to be that way so it will go to any length to associate itself with other nuclei and electrons. In this way hydrogen readily enters quantum or condensed states. In hydrogen loving metals hydrogen is just fine seeing its electron partner go galavanting about so long as it has other protons to commisurate with. Hence hydrogen will form into Bose Einstein or perhaps Rydberg Book Clubs at the drop of a hat in metals or perhaps it will just form up with one other as a Cooper pair.